It’s easy to scoff at accusations of the promotion of witchcraft in the Harry Potter series, or of pornography in Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson. But defending a book on the Banned Books list from charges that the author confirms—well, that’s a horse of a different color! Or is it?

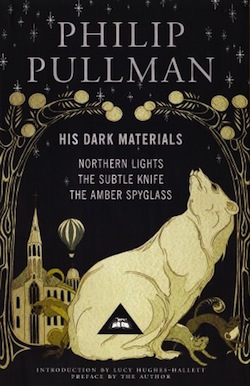

Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series was number 8 on the Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books list for 2000-2009. In 2007, the Catholic League campaigned against The Golden Compass, declaring that it promoted atheism and attacked Christianity, in particular the Catholic church. In a later interview with the Guardian Pullman partially confirmed this, saying “In one way, I hope the wretched organisation will vanish entirely.”

But he’s also made it clear that it’s not God or religion he objects to, rather the way that the structures and ideas are used for ill:

“[I]n my view, belief in God seems to be a very good excuse, on the part of those who claim to believe, for doing many wicked things that they wouldn’t feel justified in doing without such a belief.”

I didn’t encounter His Dark Materials until I was in my 20s, but dove into it with glee—I don’t think I’ll ever outgrow a delight in magical worlds just a hop, skip, and a jump away from our own. Whether Lyra was scrambling around Oxford, trekking across frozen wastes, or plunging into the Land of the Dead, I was right there behind her, pulled along by the story. I could ask for no better companions than Iorek Byrnison and Lee Scoresby, and I doubt I’m alone in having devoted time to considering what shape my daemon would take. There are as many ways to read a book as there are readers, and what I got out it was a sense of adventure, the importance of a personal moral compass, and a lot of fond daydreams. The religious controversy over the books passed me by until I went looking—as there was plenty of talk about religion in my life growing up, I’ve never felt a need to go looking for it in fiction. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t there.

One could argue that while the disdain for organized religion and bureaucracy registers in Pullman’s books as well as in his interviews, it doesn’t prevent them from containing all kinds of mystical elements. There are witches with super powers, embodied souls in the form of daemons, a trip to the underworld. One could further say that they promote a sense of spirituality and a belief in the possibility of things beyond our comprehension. There’s a word for that; some call it faith. This argument, of course, is unlikely to hold weight with anyone who objects to the series. In matters of taste there can be no dispute, and each reader finds something different in a book. Pullman himself said it best, as part of a Q&A:

“Whatever I told you would have little importance compared to what the story itself is telling you. Attend to that, and I don’t matter at all.”

The ultimate point of celebrating Banned Books Week is not to defend challenged books against specific charges, but to celebrate the freedom to read. And the freedom to read includes the freedom to read books that are maybe a little old for us, or over our heads, or take us in a direction we weren’t planning on going. To read books that contain ideas that we might not agree with, and to sharpen our own ideas by comparison. The freedom to find our own way, to have adventures and get a little lost and then find our way back, and be the wiser for it—just like Lyra.

Banned Books Week 2013 is being celebrated from Sept. 22 to the 28; further information on Banned and Frequently Challenged Books is available from the American Library Association.

Jenn Northington is an independent bookseller, the events director for WORD bookstores, and comes from a long line of nerds.